This blog was created to show children that science can be very much more fun than what they are used to think of it.

viernes, 21 de agosto de 2009

viernes, 10 de julio de 2009

martes, 30 de junio de 2009

miércoles, 27 de mayo de 2009

viernes, 22 de mayo de 2009

miércoles, 13 de mayo de 2009

viernes, 24 de abril de 2009

lunes, 16 de marzo de 2009

jueves, 5 de marzo de 2009

miércoles, 4 de marzo de 2009

lunes, 2 de marzo de 2009

viernes, 27 de febrero de 2009

lunes, 2 de febrero de 2009

PROPERTIES OF THE GROUPS OF THE PERIODIC TABLE

Alkali Metals

Properties of Element Groups

The alkali metals exhibit many of the physical properties common to metals, although their densities are lower than those of other metals. Alkali metals have one electron in their outer shell, which is loosely bound. This gives them the largest atomic radii of the elements in their respective periods. Their low ionization energies result in their metallic properties and high reactivities. An alkali metal can easily lose its valence electron to form the univalent cation. Alkali metals have low electronegativities. They react readily with nonmetals, particularly halogens.

Summary of Common Properties

· Lower densities than other metals

· One loosely bound valence electron

· Largest atomic radii in their periods

· Low ionization energies

· Low electronegativities

· Highly reactive

Metals

Properties

Metals are shiny solids are room temperature (except mercury), with characteristic high melting points and densities. Many of the properties of metals, including large atomic radius, low ionization energy, and low electronegativity, are due to the fact that the electrons in the valence shell of a metal atoms can be removed easily. One characteristic of metals is their ability to be deformed without breaking. Malleability is the ability of a metal to be hammered into shapes. Ductility is the ability of a metal to be drawn into wire. Because the valence electrons can move freely, metals are good heat conductors and electrical conductors.

Summary of Common Properties

· Shiny 'metallic' appearance

· Solids at room temperature (except mercury)

· High melting points

· High densities

· Large atomic radii

Nonmetals

Properties

Nonmetals have high ionization energies and electronegativities. They are generally poor conductors of heat and electricity. Solid nonmetals are generally brittle, with little or no metallic luster. Most nonmetals have the ability to gain electrons easily. Nonmetals display a wide range of chemical properties and reactivities.

Summary of Common Properties

· High ionization energies

· High electronegativities

· Poor thermal conductors

· Poor electrical conductors

· Brittle solids

· Little or no metallic luster

· Gain electrons easily

Metalloids or Semimetals

Properties

The electronegativities and ionization energies of the metalloids are between those of the metals and nonmetals, so the metalloids exhibit characteristics of both classes. Silicon, for example, possesses a metallic luster, yet it is an inefficient conductor and is brittle. The reactivity of the metalloids depends on the element with which they are reacting. For example, boron acts as a nonmetal when reacting with sodium yet as a metal when reacting with fluorine. The boiling points, melting points, and densities of the metalloids vary widely. The intermediate conductivity of metalloids means they tend to make good semiconductors.

Summary of Common Properties

· Electronegativities between those of metals and nonmetals

· Ionization energies between those of metals and nonmetals

· Possess some characteristics of metals/some of nonmetals

· Reactivity depends on properties of other elements in reaction

· Often make good semiconductors

Alkaline Earth Metals

The alkaline earths possess many of the characteristic properties of metals. Alkaline earths have low electron affinities and low electronegativities. As with the alkali metals, the properties depend on the ease with which electrons are lost. The alkaline earths have two electrons in the outer shell. They have smaller atomic radii than the alkali metals. The two valence electrons are not tightly bound to the nucleus, so the alkaline earths readily lose the electrons to form divalent cations.

Summary of Common Properties

· Two electrons in the outer shell

· Low electron affinities

· Low electronegativities

· Readily form divalent cations.

Transition Metals

Because they possess the properties of metals, the transition elements are also known as the transition metals. These elements are very hard, with high melting points and boiling points. Moving from left to right across the periodic table, the five d orbitals become more filled. The d electrons are loosely bound, which contributes to the high electrical conductivity and malleability of the transition elements. The transition elements have low ionization energies. They exhibit a wide range of oxidation states or positively charged forms. The positive oxidation states allow transition elements to form many different ionic and partially ionic compounds. The formation of complexes causes the d orbitals to split into two energy sublevels, which enables many of the complexes to absorb specific frequencies of light. Thus, the complexes form characteristic colored solutions and compounds. Complexation reactions sometimes enhance the relatively low solubility of some compounds.

Summary of Common Properties

· Low ionization energies

· Positive oxidation states

· Very hard

· High melting points

· High boiling points

· High electrical conductivity

· Malleable

HALOGENS

These reactive nonmetals have seven valence electrons. As a group, halogens exhibit highly variable physical properties. Halogens range from solid (I2) to liquid (Br2) to gaseous (F2 and Cl2) at room temperature. The chemical properties are more uniform. The halogens have very high electronegativities. Fluorine has the highest electronegativity of all elements. The halogens are particularly reactive with the alkali metals and alkaline earths, forming stable ionic crystals.

Summary of Common Properties

· Very high electronegativities

· Seven valence electrons (one short of a stable octet)

· Highly reactive, especially with alkali metals and alkaline earths

NOBLE GASSES

Location on the Periodic Table

The noble gases, also known as the inert gases, are located in Group VIII of the periodic table. Group VIII is sometimes called Group O.

Properties

The noble gases are relatively nonreactive. This is because they have a complete valence shell. They have little tendency to gain or lose electrons. The noble gases have high ionization energies and negligible electronegativities. The noble gases have low boiling points and are all gases at room temperature.

Summary of Common Properties

· Fairly nonreactive

· Complete valence shell

· High ionization energies

· Very low electronegativities

· Low boiling points (all gases at room temperature)

RARE EARTH

The Bottom of the Periodic Table

When you look at the Periodic Table, there is a block of two rows of elements located below the main body of the chart. These elements, plus lanthanum (element 57) and actinium (element 89), are known collectively as the rare earth elements or rare earth metals. Actually, they aren't particularly rare, but prior to 1945, long and tedious processes were required to purify the metals from their oxides. Ion-exchange and solvent extraction processes are used today to quickly produce highly pure, low-cost rare earths, but the old name is still in use. The rare earth metals are found in group 3 of the periodic table, and the 6th (5d electronic configuration) and 7th (5f electronic configuration) periods. There are some arguments for starting the 3rd and 4th transition series with lutetium and lawrencium rather than lanthanum and actinium.

There are two blocks of rare earths, the lanthanide series and the actinide series. Lanthanum and actinium are both located in group IIIB of the table. When you look at the periodic table, notice that the atomic numbers make a jump from lanthanum (57) to hafnium (72) and from actinium (89) to rutherfordium (104). If you skip down to the bottom of the table, you can follow the atomic numbers from lanthanum to cerium and from actinium to thorium, and then back up to the main body of the table. Some chemists exclude lanthanum and actinium from the rare earths, considering the lanthanides to start following lanthanum and the actinides to start following actinium. In a way, the rare earths are special transition metals, possessing many of the properties of these elements.

Common Properties of the Rare Earths

These common properties apply to both the lanthanides and actinides.

· The rare earths are silver, silvery-white, or gray metals.

· The metals have a high luster, but tarnish readily in air.

· The metals have high electrical conductivity.

· The rare earths share many common properties. This makes them difficult to separate or even distinguish from each other.

· There are very small differences in solubility and complex formation between the rare earths.

· The rare earth metals naturally occur together in minerals (e.g., monazite is a mixed rare earth phosphate).

· Rare earths are found with non-metals, usually in the 3+ oxidation state. There is little tendency to vary the valence. (Europium also has a valence of 2+ and cerium also a valence of 4+.)

LANTHANIDES

The D Block Elements

The lanthanides are located in block 5d of the periodic table. The first 5d transition element is either lanthanum or lutetium, depending on how you interpret the periodic trends of the elements. Sometimes only the lanthanides, and not the actinides, are classified as rare earths. The lanthanides are not as rare as was once thought; even the scarce rare earths (e.g., europium, lutetium) are more common than the platinum-group metals. Several of the lanthanides form during the fission of uranium and plutonium.

The lanthanides have many scientific and industrial uses. Their compounds are used as catalysts in the production of petroleum and synthetic products. Lanthanides are used in lamps, lasers, magnets, phosphors, motion picture projectors, and X-ray intensifying screens. A pyrophoric mixed rare-earth alloy called Mischmetall (50% Ce, 25% La, 25% other light lanthanides) or misch metal is combined with iron to make flints for cigarette lighters. The addition of <1% Mischmetall or lanthanide silicides improves the strength and workability of low alloy steels.

Common Properties of the Lanthanides

Lanthanides share the following common properties:

· Silvery-white metals that tarnish when exposed to air, forming their oxides.

· Relatively soft metals. Hardness increases somewhat with higher atomic number.

· Moving from left to right across the period (increasing atomic number), the radius of each lanthanide 3+ ion steadily decreases. This is referred to as 'lanthanide contraction'.

· High melting points and boiling points.

· Very reactive.

· React with water to liberate hydrogen (H2), slowly in cold/quickly upon heating. Lanthanides commonly bind to water.

· React with H+ (dilute acid) to release H2 (rapidly at room temperature).

· React in an exothermic reaction with H2.

· Burn easily in air.

· They are strong reducing agents.

· Their compounds are generally ionic.

· At elevated temperatures, many rare earths ignite and burn vigorously.

· Most rare earth compounds are strongly paramagnetic.

· Many rare earth compounds fluoresce strongly under ultraviolet light.

· Lanthanide ions tend to be pale colors, resulting from weak, narrow, forbidden f x f optical transitions.

· The magnetic moments of the lanthanide and iron ions oppose each other.

· The lanthanides react readily with most nonmetals and form binaries on heating with most nonmetals.

ACTINIDES

The F Block Elements

The electronic configurations of the actinides utilize the f sublevel. Depending on your interpretation of the periodicity of the elements, the series begins with actinium, thorium, or even lawrencium. The actinides (An) are prepared by reduction of AnF3 or AnF4 with vapors of Li, Mg, Ca, or Ba at 1100 - 1400°C.

Common Properties of the Actinides

Actinides share the following common properties:

· All are radioactive.

· Actinides are highly electropositive.

· The metals tarnish readily in air.

· Actinides are very dense metals with distinctive structures. Numerous allotropes may be formed (plutonium has at least 6 allotropes!).

· They react with boiling water or dilute acid to release hydrogen gas.

· Actinides combine directly with most nonmetals.

Properties of Element Groups

The alkali metals exhibit many of the physical properties common to metals, although their densities are lower than those of other metals. Alkali metals have one electron in their outer shell, which is loosely bound. This gives them the largest atomic radii of the elements in their respective periods. Their low ionization energies result in their metallic properties and high reactivities. An alkali metal can easily lose its valence electron to form the univalent cation. Alkali metals have low electronegativities. They react readily with nonmetals, particularly halogens.

Summary of Common Properties

· Lower densities than other metals

· One loosely bound valence electron

· Largest atomic radii in their periods

· Low ionization energies

· Low electronegativities

· Highly reactive

Metals

Properties

Metals are shiny solids are room temperature (except mercury), with characteristic high melting points and densities. Many of the properties of metals, including large atomic radius, low ionization energy, and low electronegativity, are due to the fact that the electrons in the valence shell of a metal atoms can be removed easily. One characteristic of metals is their ability to be deformed without breaking. Malleability is the ability of a metal to be hammered into shapes. Ductility is the ability of a metal to be drawn into wire. Because the valence electrons can move freely, metals are good heat conductors and electrical conductors.

Summary of Common Properties

· Shiny 'metallic' appearance

· Solids at room temperature (except mercury)

· High melting points

· High densities

· Large atomic radii

Nonmetals

Properties

Nonmetals have high ionization energies and electronegativities. They are generally poor conductors of heat and electricity. Solid nonmetals are generally brittle, with little or no metallic luster. Most nonmetals have the ability to gain electrons easily. Nonmetals display a wide range of chemical properties and reactivities.

Summary of Common Properties

· High ionization energies

· High electronegativities

· Poor thermal conductors

· Poor electrical conductors

· Brittle solids

· Little or no metallic luster

· Gain electrons easily

Metalloids or Semimetals

Properties

The electronegativities and ionization energies of the metalloids are between those of the metals and nonmetals, so the metalloids exhibit characteristics of both classes. Silicon, for example, possesses a metallic luster, yet it is an inefficient conductor and is brittle. The reactivity of the metalloids depends on the element with which they are reacting. For example, boron acts as a nonmetal when reacting with sodium yet as a metal when reacting with fluorine. The boiling points, melting points, and densities of the metalloids vary widely. The intermediate conductivity of metalloids means they tend to make good semiconductors.

Summary of Common Properties

· Electronegativities between those of metals and nonmetals

· Ionization energies between those of metals and nonmetals

· Possess some characteristics of metals/some of nonmetals

· Reactivity depends on properties of other elements in reaction

· Often make good semiconductors

Alkaline Earth Metals

The alkaline earths possess many of the characteristic properties of metals. Alkaline earths have low electron affinities and low electronegativities. As with the alkali metals, the properties depend on the ease with which electrons are lost. The alkaline earths have two electrons in the outer shell. They have smaller atomic radii than the alkali metals. The two valence electrons are not tightly bound to the nucleus, so the alkaline earths readily lose the electrons to form divalent cations.

Summary of Common Properties

· Two electrons in the outer shell

· Low electron affinities

· Low electronegativities

· Readily form divalent cations.

Transition Metals

Because they possess the properties of metals, the transition elements are also known as the transition metals. These elements are very hard, with high melting points and boiling points. Moving from left to right across the periodic table, the five d orbitals become more filled. The d electrons are loosely bound, which contributes to the high electrical conductivity and malleability of the transition elements. The transition elements have low ionization energies. They exhibit a wide range of oxidation states or positively charged forms. The positive oxidation states allow transition elements to form many different ionic and partially ionic compounds. The formation of complexes causes the d orbitals to split into two energy sublevels, which enables many of the complexes to absorb specific frequencies of light. Thus, the complexes form characteristic colored solutions and compounds. Complexation reactions sometimes enhance the relatively low solubility of some compounds.

Summary of Common Properties

· Low ionization energies

· Positive oxidation states

· Very hard

· High melting points

· High boiling points

· High electrical conductivity

· Malleable

HALOGENS

These reactive nonmetals have seven valence electrons. As a group, halogens exhibit highly variable physical properties. Halogens range from solid (I2) to liquid (Br2) to gaseous (F2 and Cl2) at room temperature. The chemical properties are more uniform. The halogens have very high electronegativities. Fluorine has the highest electronegativity of all elements. The halogens are particularly reactive with the alkali metals and alkaline earths, forming stable ionic crystals.

Summary of Common Properties

· Very high electronegativities

· Seven valence electrons (one short of a stable octet)

· Highly reactive, especially with alkali metals and alkaline earths

NOBLE GASSES

Location on the Periodic Table

The noble gases, also known as the inert gases, are located in Group VIII of the periodic table. Group VIII is sometimes called Group O.

Properties

The noble gases are relatively nonreactive. This is because they have a complete valence shell. They have little tendency to gain or lose electrons. The noble gases have high ionization energies and negligible electronegativities. The noble gases have low boiling points and are all gases at room temperature.

Summary of Common Properties

· Fairly nonreactive

· Complete valence shell

· High ionization energies

· Very low electronegativities

· Low boiling points (all gases at room temperature)

RARE EARTH

The Bottom of the Periodic Table

When you look at the Periodic Table, there is a block of two rows of elements located below the main body of the chart. These elements, plus lanthanum (element 57) and actinium (element 89), are known collectively as the rare earth elements or rare earth metals. Actually, they aren't particularly rare, but prior to 1945, long and tedious processes were required to purify the metals from their oxides. Ion-exchange and solvent extraction processes are used today to quickly produce highly pure, low-cost rare earths, but the old name is still in use. The rare earth metals are found in group 3 of the periodic table, and the 6th (5d electronic configuration) and 7th (5f electronic configuration) periods. There are some arguments for starting the 3rd and 4th transition series with lutetium and lawrencium rather than lanthanum and actinium.

There are two blocks of rare earths, the lanthanide series and the actinide series. Lanthanum and actinium are both located in group IIIB of the table. When you look at the periodic table, notice that the atomic numbers make a jump from lanthanum (57) to hafnium (72) and from actinium (89) to rutherfordium (104). If you skip down to the bottom of the table, you can follow the atomic numbers from lanthanum to cerium and from actinium to thorium, and then back up to the main body of the table. Some chemists exclude lanthanum and actinium from the rare earths, considering the lanthanides to start following lanthanum and the actinides to start following actinium. In a way, the rare earths are special transition metals, possessing many of the properties of these elements.

Common Properties of the Rare Earths

These common properties apply to both the lanthanides and actinides.

· The rare earths are silver, silvery-white, or gray metals.

· The metals have a high luster, but tarnish readily in air.

· The metals have high electrical conductivity.

· The rare earths share many common properties. This makes them difficult to separate or even distinguish from each other.

· There are very small differences in solubility and complex formation between the rare earths.

· The rare earth metals naturally occur together in minerals (e.g., monazite is a mixed rare earth phosphate).

· Rare earths are found with non-metals, usually in the 3+ oxidation state. There is little tendency to vary the valence. (Europium also has a valence of 2+ and cerium also a valence of 4+.)

LANTHANIDES

The D Block Elements

The lanthanides are located in block 5d of the periodic table. The first 5d transition element is either lanthanum or lutetium, depending on how you interpret the periodic trends of the elements. Sometimes only the lanthanides, and not the actinides, are classified as rare earths. The lanthanides are not as rare as was once thought; even the scarce rare earths (e.g., europium, lutetium) are more common than the platinum-group metals. Several of the lanthanides form during the fission of uranium and plutonium.

The lanthanides have many scientific and industrial uses. Their compounds are used as catalysts in the production of petroleum and synthetic products. Lanthanides are used in lamps, lasers, magnets, phosphors, motion picture projectors, and X-ray intensifying screens. A pyrophoric mixed rare-earth alloy called Mischmetall (50% Ce, 25% La, 25% other light lanthanides) or misch metal is combined with iron to make flints for cigarette lighters. The addition of <1% Mischmetall or lanthanide silicides improves the strength and workability of low alloy steels.

Common Properties of the Lanthanides

Lanthanides share the following common properties:

· Silvery-white metals that tarnish when exposed to air, forming their oxides.

· Relatively soft metals. Hardness increases somewhat with higher atomic number.

· Moving from left to right across the period (increasing atomic number), the radius of each lanthanide 3+ ion steadily decreases. This is referred to as 'lanthanide contraction'.

· High melting points and boiling points.

· Very reactive.

· React with water to liberate hydrogen (H2), slowly in cold/quickly upon heating. Lanthanides commonly bind to water.

· React with H+ (dilute acid) to release H2 (rapidly at room temperature).

· React in an exothermic reaction with H2.

· Burn easily in air.

· They are strong reducing agents.

· Their compounds are generally ionic.

· At elevated temperatures, many rare earths ignite and burn vigorously.

· Most rare earth compounds are strongly paramagnetic.

· Many rare earth compounds fluoresce strongly under ultraviolet light.

· Lanthanide ions tend to be pale colors, resulting from weak, narrow, forbidden f x f optical transitions.

· The magnetic moments of the lanthanide and iron ions oppose each other.

· The lanthanides react readily with most nonmetals and form binaries on heating with most nonmetals.

ACTINIDES

The F Block Elements

The electronic configurations of the actinides utilize the f sublevel. Depending on your interpretation of the periodicity of the elements, the series begins with actinium, thorium, or even lawrencium. The actinides (An) are prepared by reduction of AnF3 or AnF4 with vapors of Li, Mg, Ca, or Ba at 1100 - 1400°C.

Common Properties of the Actinides

Actinides share the following common properties:

· All are radioactive.

· Actinides are highly electropositive.

· The metals tarnish readily in air.

· Actinides are very dense metals with distinctive structures. Numerous allotropes may be formed (plutonium has at least 6 allotropes!).

· They react with boiling water or dilute acid to release hydrogen gas.

· Actinides combine directly with most nonmetals.

miércoles, 21 de enero de 2009

LA BIODIVERSIDAD EN COLOMBIA

Biodiversidad en Colombia

De acuerdo con el Convenio sobre la Diversidad Biológica, el término biodiversidad “…se entiende la variabilidad de organismos vivos de cualquier fuente, incluidos, entre otras cosas, los ecosistemas terrestres y marinos y otros ecosistemas acuáticos y los complejos ecológicos de los que forman parte; comprende la diversidad dentro de cada especie, entre las especies y de los ecosistemas”, y por ecosistema se entiende “…un complejo dinámico de comunidades vegetales, animales y de microorganismos y su medio no viviente que interactúan como una unidad funcional.”

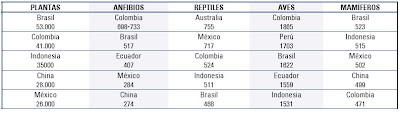

Aunque no existen inventarios biológicos detallados y completos para todo el país, sí se conoce que a nivel de especies, Colombia es considerada como la cuarta nación en biodiversidad mundial siendo por grupo taxonómico, el segundo en biodiversidad a nivel de plantas, primera en anfibios y aves, tercera en reptiles y quinto en mamíferos

Un total de 3.357 especies de peces (Maldonado y Usma 2006), anfibios, reptiles, aves y mamíferos y cerca de 41.000 especies de plantas han sido registradas para Colombia. Esta biodiversidad varía de acuerdo con las regiones naturales del país, siendo la andina la que presenta mayor diversidad en grupos como anfibios, reptiles, aves, mamíferos y plantas, con un total de 13.505 spp., (29,4%), seguida de la Amazonia, 7.215 spp. (15,7%), Pacífica, 5.927 spp. (12,9%), Caribe, 4.440 spp. (9,7%) y Orinoquia 4.216 spp. (9.2%). Para peces la región Amazónica presenta la mayor diversidad con un 49,7% de especies seguida de la Orinoquia con 45,6%, Andina (45,6%), Pacífica (12,1%) y caribe (8,03%). En aves la región andina tiene una diversidad de 52.2% seguida de la región Caribe (50.9%), Amazónica (46,5%), Pacífica (44,5%) y Orinoquia (34,5%)

En el caso de anfibios, la región andina tiene 53% de diversidad, seguida del Pacífico (27,3%), Amazónico (19,6%), Orinoquia (5,7%) y Caribe (3.9%). En reptiles, el 52.9% está en los Andes, seguida de región Pacífica (40%), Amazónica (28%), Orinoquia (23%) y Caribe (19%). En el caso de mamíferos con 37.6% se encuentra la región Andina seguida del Pacífico (35.5%), Orinoquia (21,4%), Caribe (21,2%) y Amazónica (18%). Por último, en plantas, después de la región andina, el segundo lugar lo tiene la región Amazónica (13%), seguida del Pacífico (11%), Caribe (7.7%) y Orinoquia (6.6%)

lunes, 19 de enero de 2009

EL REGALO DEL SALMON EN ESPAÑOL

LOS BIÓLOGOS ESTÁN APRENDIENDO QUE CUANDO LOS SALMONES SON LIBRES DE NADAR RIO ARRIBA PARA DESOVAR, OTRAS ESPECIES TAMBIÉN PROSPERAN

MI HIJO Y YO CAPOTEAMOS RIO ARRIBA CALZADOS CON BOTAS HASTA LA CADERA, buscando señales del salmón que regresa cada verano a desovar y morir en este riachuelo salvaje de Alaska. Yo he venido aquí para comprobar personalmente lo que él escribió acerca de esto el año pasado:

El riachuelo está tan lleno de salmones que constituye un reto caminar río arriba. Yo tropiezo y resbalo sobre los salmones muertos que se encuentran sobre la grava del fondo. Es como caminar sobre piernas humanas. Cuando accidentalmente piso un pez muerto, gime, dejando escapar el gas atrapado. En las aguas poco profundas los peces me golpean las botas, los arrastra la corriente y tropiezan con mis tobillos. Las gaviotas abundan y lanzan sus graznidos río arriba, señal de que los osos pardos están pescando. El riachuelo apesta a muerte.

Hoy toda la corriente esta limpia y reluciente. Nos movemos lentamente a lo largo de la grava contemplando los gorriones de corona dorada hasta que Jon se agacha y recoge una sencilla vértebra de salmón blanqueada. Excepto esto, todas las evidencias de salmón han desaparecido. ¿A dónde fueron a parar las pilas de salmones muertos que él vio? ¿Qué efectos producen su vida y su muerte sobre la salud de todo este ecosistema?

Jon, graduado de ecología acuática, trabajo los veranos con el Programa de Salmón de Alaska, de la Universidad de Washington, un proyecto de investigación que comenzó en 1946. Los científicos del programa y sus colegas de otras instituciones, están hallando que el salmón, al engordar en el océano y nadar de regreso a los riachuelos y lagos de agua dulce, trae energía y nutrientes río arriba en un amplio sistema de recirculación, que vigoriza la vida vegetal y animal a lo largo de esas vías acuáticas. Los nutrientes dejan un registro químico en el fondo de los lagos, que indica las altas y bajas de las poblaciones de salmón y podría ofrecer claves acerca de los patrones de cambios climatológicos.

En la mayor parte de los ríos costeros de América del Norte, alguna vez pulularon grandes cantidades de peces anádromos, organismos que nacen en las corrientes de agua dulce tierra adentro, emigran al mar salado y regresan a las corrientes fluviales a desovar. Durante más de 10.000 años, los peces migratorios, el chinuk del Atlántico y el salmón, el sábalo americano, el arenque de lomo azul y la perca rayada, para mencionar unos pocos, han regresado en una cantidad asombrosa a los grandes ríos tanto en las costas del Pacífico como del Atlántico, pero muchos de estos han desaparecido, eliminados en sólo un siglo. Los estudios acerca de los ríos no deteriorados de Alaska podrían ayudar a explicar cómo un ecosistema sufre cuando pierde los movimientos río arriba de los peces.

JON TRABAJA EN UNA CABAÑA GRIS, CLIMATIZADA, DETRÁS DE UNA PLAYA en un lago de montaña, conectado al mar por ríos. Capas amarillas para la lluvia, calcetines mojados y abrigos anaranjados y brillosos cuelgan de perchas al frente de la cabaña y una canoa, mordisqueada por los osos descansa boca abajo junto a la ventana. Jon está sentado en un banco junto a la puerta principal y mientras se quita las botas, explica lo que los científicos están aprendiendo.

La gente está acostumbrada a pensar que los ríos fluyen solamente hacia el mar, dice. Una hoja o un insecto caen al agua, la corriente erosiona un banco, una sardina se muere y el río se lleva muchos de esos nutrientes hacia el océano. Lo que el salmón hace al nadar río arriba es invertir este flujo de nutrientes.

“El salmón adquiere más del 95 por ciento de su masa en el océano, para después nadar río arriba y morir”, dice Daniel Schindler, cuando hago contacto con él por radio. Schindler es un ecólogo acuático de la Universidad de Washington y científico del Programa del Salmón de Alaska. “El pez mueve energía y nutrientes contracorriente, haciendo que el río de nutrientes fluya del océano aguas arriba, compensando los nutrientes que la gravedad se lleva”. Los nutrientes son la materia prima de la vida, necesarios para las funciones vitales de todos, desde el crecimiento de una neurona hasta el reverdecer de las hojas.

Cuando existen grandes poblaciones de salmón, el retorno de nutrientes puede ser inmenso. Ted Grez, consultor ambientalista de Pórtland, Oregon, estima que durante las corridas históricas en el Pacífico Noroccidental, 225 millones de kilogramos de salmón regresaron a desovar y morir cada año. Los investigadores estiman que en el Río Columbia solamente, el salmón contribuyó con cientos de miles de kilogramos de nitrógeno y fósforo anuales en esa cuenca.

En la actualidad, camiones y barcazas transportan fertilizantes manufacturados río arriba por el Columbia. La pesca excesiva, las presas, la destrucción del hábitat y la competencia de los criaderos de peces han dañado las corridas de los salmones salvajes. A través del noroeste, los ríos reciben como promedio, sólo el 6 por ciento de los nutrientes que recibían un siglo atrás, una dramática hambruna.

EL EQUIPO EN EL QUE TRABAJA JON ESTA TRATANDO DE COMPRENDER como, en una corriente saludable, los vectores esparcen nutrientes del salmón a todo el ecosistema. Un vector es cualquier cosa que mueva nutrientes de un lado para otro, incluyendo la inundación que traslada un cadáver al bosque, un oso que se harta de salmón y luego defeca en la tundra o cualquier carroñero que come en un lugar y posteriormente orina, defeca o se muere en otro. Aun las larvas son vectores, a juzgar por las notas de Jon:

Cuando levanto un salmón que murió hace dos días, es sólo una piel de salmón rellena de larvas. Oigo a las larvas escarbando bajo la piel, haciéndola retorcerse y pulsar. Las larvas se caen de las cuencas oculares. Tan pronto un salmón muere las moscas carroñeras penetran por su boca y sus agallas y ponen huevos. Los huevos se transforman rápidamente en larvas que devoran al salmón a una velocidad alarmante. En sólo cuatro días un salmón muerto se transforma en 10.000 larvas. Salen del salmón contorsionándose y caen en la tierra, donde eventualmente se transforman en moscas adultas, que revolotean alrededor de las corrientes, zumbando en nuestras caras.

Las arañas y las aves se comen estas moscas voladoras. Algunas larvas caen en el río, donde las devoran el salmón del Ártico y la trucha arco iris.

Durante el pico del desove de los salmones, numerosas criaturas convergen en el rió y se ponen a trabajar. El visón que habita en las cercanías de una corriente saludable con salmones, adapta su ciclo reproductivo al surgimiento estacional del salmón, según Merav Ben-David, ecóloga de comportamiento de la Universidad de Alaska en Faribanks. Ella halló que el visón hembra comienza la lactancia, un cambio energético notable, cuando los cadáveres de salmón son más abundantes. Un informe del Departamento de Recursos Naturales de Washington identifica a 66 vertebrados que se alimentan de salmón. Los salmones jóvenes también comen salmones muertos. La investigación de Robert Bilby, un ecólogo acuático de Wyerhaeuser Company, muestra que hasta el 78 por ciento del contenido estomacal de los salmones jóvenes lo constituyen cadáveres de salmón y huevas. Las notas de Jon describen el frenesí alimentario que ocurre cuando los salmones están desovando:

En los bancos del río donde hay salmones, tropezamos con osos, helechos y hierbas pisoteadas, así como partes descompuestas de salmón, donde los osos los arrastraron para comerlos. Las gaviotas pasan mucho trabajo para abrir los salmones por sí mismas, por lo que bandadas de ellas siguen a los osos, esperando la oportunidad de comerse los restos. Las gaviotas hacen sus nidos en islas expuestas que pronto se llenan de espinas de salmón. A medida que los polluelos crecen y engordan, la isla se va librando del salmón digerido, pues la lluvia arrastra el guano hacia el lago.

Las águilas calvas despedazan el salmón para llevar alimento a sus polluelos. Las larvas de moscas se alimentan de los cadáveres del salmón bajo el agua, para después convertirse en adultos que salen volando. La trucha arco iris se alimenta de la carne de salmón que se desprende lentamente de los salmones en descomposición. El visón engulle los peces que ya han desovado. Los árboles crecen rápidamente con todo este fertilizante. Los turistas vienen en aviones anfibios para pescar, tirándoles las vísceras a las grullas y congelando los filetes en cajas de cartón encerado para llevarlas de vuelta a Tacoma o St. Louis.

Hace tres días, cuando llegamos aquí, a las piscinas alimentadas por el riachuelo, contamos 216 salmones, con sus lomos sobresaliendo del agua poco profunda. Las hembras cavaban sus nidos y los machos luchaban por las hembras. Se colocaban lado a lado con sus quijadas saliendo del agua. De pronto se desató un infierno. Un salmón agarró a otro con sus dientes, lo sacudió como un buldog, lanzando al pez más débil por el agua.

Hoy, en la misma piscina hay sólo tres salmones vivos, el resto lo mataron los osos. Los tres salmones sobrevivientes nadan lentamente a través de la masacre.

Se siente como si hubiera osos por todas partes. En una esquina hallo huellas frescas en la arena, que se llenan lentamente de agua y sangre.

Para analizar la importancia histórica del salmón en la dieta de los Osos pardos, Grant Hildebrand, biólogo investigador que trabaja para el Departamento de Caza y Pesca de Alaska, utilizó técnicas de muestreo de nitrógeno. Para determinar qué parte del nitrógeno de un ecosistema proviene del salmón, los científicos miden los isótopos estables. El nitrógeno en el medio terrestre y en el agua dulce se compone principalmente del isótopo más ligero N-14, con poco del más pesado -15. El salmón, sin embargo, tiene una relación relativamente alta de N-15 a N-14, comparada con las fuentes de fijación de nitrógeno como los árboles. De esa forma, los científicos pueden estimar la cantidad de nitrógeno que proviene del salmón, midiendo las relaciones de N.-15 a N-14 en cualquier tejido que recolecten, desde pelos de alce hasta hojas de sauce.

Hildebrand y sus colegas cortaron pelos y huesos de osos pardos que llevaban tiempo muertos y los expusieron en lugares como el Museo Americano de Historia Natural en New York. Hallaron que entre 1856 y 1931, del 33 al 90 por ciento del nitrógeno de los osos provenía del salmón, hasta en lugares tan lejanos tierra adentro como Idaho. Actualmente las corridas de salmón en los 48 estados continentales se han reducido drásticamente, igual que los osos.

En Alaska parece haber gran cantidad de osos. Jon y yo los hemos visto todos los días patrullando las playas, ocupándose de lo suyo, esperando, al igual que nosotros, que regresen los salmones. Una mañana Jon y yo terminamos encaramados, como las golondrinas, en la punta más alta del tejado de la estación. Yo tenía en cada mano una lata gigante de atomizador para osos y Jon revisaba los arbustos con unos binoculares.

Acabábamos de arrimar el bote a la orilla de la playa del campamento cuando un oso salió de los árboles y cargó hacia el bote. Jon estaba junto a la puerta de la cabaña, mientras yo estaba haciendo algo con mi cámara fotográfica junto a la playa. Oí a Jon decir, en una voz que los hijos usualmente no utilizan con sus madres: “Entra en la cabaña”. Yo lo hice. Subimos por una escalera hasta la azotea para tratar de ver al oso, pero ya había desaparecido. Ahora estamos sentados aquí. No se ve movimiento en los arbustos.

Mientras observo la playa de grava, la ensenada azul, las islas de roca blanqueada y las gaviotas planeadoras, comienzo a entender que la corriente que los científicos estudian no es un simple riachuelo. Es un río de energía que se mueve a través de regiones en grandes ciclos geográficos. Aquí la vida y la muerte son sólo diferentes puntos de una continuidad. El río fluye en un círculo a través del tiempo y el espacio, convirtiendo la muerte en vida a lo largo de los ecosistemas costeros, como lo ha estado haciendo durante más de un millón de años, pero estas corrientes ya no fluyen en los lugares donde la mayoría de nosotros vivimos.

EL DÍA SIGUIENTE LLUEVE. NOS PONEMOS LAS BOTAS Y LOS IMPERMEABLES y nos montamos en el bote para dirigirnos a otro riachuelo en busca de salmón. Caminar río arriba es duro, las rocas resbalan debido a las algas. En las piscinas tranquilas, el fango da al tobillo y al caminar se levantan densos remolinos de cieno.

Después que los salmones desoven el lecho del río quedará tan limpio como un camino de grava. A medida que la hembra del salmón escarba los nidos donde pondrá los huevos, ayuda a crear las condiciones en las cuales sus huevos prosperan, un lecho de grava limpia bajo el agua en movimiento. Se acuesta de lado y bate su cola violentamente contra el lecho del río, expulsando nubes de cieno. Después pone los huevos. Se traslada un corto tramo río arriba y repite la operación, eliminando algas de las rocas, quitando el cieno de los remolinos, aireando la grava. En unos pocos días todo el río estará tan limpio como si los peces lo hubieran barrido con escobas.

Aunque los salmones conforman el río, el río también conforma a los salmones. Thomas Quinn, biólogo de peces de la Universidad de Washington, dice que la forma de los peces ha evolucionado como un reflejo de las corrientes donde se encuentran, sean de 6 centímetros de profundidad o de un metro. Ser grande es riesgoso: un pez con el lomo fuera del agua tiene más probabilidades de morir en boca de un oso, pero ser grande también es una ventaja, porque una hembra tiene más probabilidades de aparearse con un gran macho. De esa forma, las corrientes poco profundas quedan para los peces pequeños, pero en los ríos más profundos o en los lagos, los salmones machos crecen tan jorobados que parecen haberse tragado platos de comer.

Para sacar conclusiones, acerca del crecimiento de los salmones en las corrientes, los cientificos necesitan conocer su edad. La edad de los salmones se calcula de forma parecida a la de los árboles, contando los anillos de los huesos del oído u otolitos, Jon describe la investigación:

Sosteniendo al salmón por las cuencas oculares vacías, escarbamos el baboso cerebro y extraemos los otolitos. Su consistencia es la de las viejas conchas marinas y su tamaño el de la uña de un bebé. Los cientificos cuentan los anillos bajo el microscopio para saber cuántos años estuvo el salmón en agua dulce y cuántos en agua de mar. Después de cortar la cabeza a cien salmones putrefactos, nuestras manos y antebrazos están resbaladizos por el cieno. Los mosquitos nos pican en la cara y en el cuello, pero no nos atrevemos a aplastarlos con nuestras manos embarradas de pescado. Los espantamos con el dorso de la muñeca.

LOS NUTRIENTES QUE EL SALMON VA DEJANDO tras sí, suministran medidas importantes acerca de los cambios en el océano. Cuando abandona el agua dulce, el salmón se propaga por todo el Pacífico, desde California hasta Japón. Permanece en el océano durante varios años, para regresar después río arriba a las piscinas que los cientificos están estudiando. “El salmón amplifica las señales del clima”, dice Schindler. Cambios muy sutiles en el océano pueden tener un efecto sustancial en las poblaciones. Un cambio de temperatura de sólo uno o os grados puede afectar a los nutrientes lo suficiente para producir una diferencia de dos o tres veces el número de salmones que regresan a los ríos.

Por eso, si los investigadores pueden graficar los cambios en el numero de salmones que nadan río arriba, pueden obtener una historia precisa de las alteraciones del océano, lo cual brinda evidencia acerca de los cambios de clima a lo largo del tiempo.

Schindler y sus colegas están buscando esa evidencia en los sedimentos de los lagos. Toman muestras cilíndricas del fondo de los lagos, donde los nutrientes se han acumulado lentamente, capa sobre capa, durante milenios. Mediante la lectura de las cantidades relativas de N-15 a cada nivel, Schindler puede leer la historia de las altas y bajas de las poblaciones de salmón.

Ha aprendido que las poblaciones de salmón aumentaron y disminuyeron a través de los siglos en ciclos complejos pero predecibles. En los lagos que Schindler estudia, los sedimentos registran una oscilación en las poblaciones de salmón de entre 50 y 70 años, pero el cuadro es complicado. Encima de las largas ondas de cambio de población, hay pequeñas ondulaciones que alcanzan un pico cada l5 a 20 años. Bruce Finney, ecólogo acuático de la Universidad de Alaska en Fairbanks, utilizó la mima técnica para demostrar que ha habido una variación mayor y mas lenta de las población de salmón. Hace 2.000 años, estas cayeron abruptamente en el Pacífico Norte. Los números se mantuvieron fijos durante 800 años para aumentar gradualmente alcanzando un pico entre los años 1200 y 1900. Finney cree que los cambios en el clima son la causa de los ciclos en las poblaciones de salmón y, mientras los cientificos tratan de entender la relación y los efectos del calentamiento global, el salmón puede ayudarlos a distinguir entre variaciones normales del clima y los primeros avisos de que un sistema se esta tornando peligrosamente negativo.

Schindler hallo que los ciclos del salmón son un reflejo del crecimiento del plancton, la base de la cadena alimentaría que sostiene la vida en un lago.

Mientras más salmón haya, más vigorosos son el zooplancton y las algas en los lagos. Sus muestras del fondo indican la caída precipitada de los niveles de plancton y de la productividad de los lagos, que marcan el inicio de la pesca en gran escala a finales del siglo XIX. Durante los últimos 100 años, la pesca ha desviado hasta dos tercios del movimiento río arriba de los nutrientes derivados del salmón, de los ecosistemas locales hacia los seres humanos.

EL ULTIMO DIA, JON ME LLEVA EN BOTE A través del lago hasta la boca del pequeño riachuelo. Sobre el lago cuelgan nubes bajas y el agua es tan sólida y brillante que parece una lámina de plata. Nos subimos a los asientos del bote ara tener una vista mejor del agua. Jon me da sus espejuelos de sol polarizados.

Señala hacia el agua profunda en la boca del río. De pronto, ahí están los salmones, cientos de ellos, de color rojo anaranjado neón. Parecen carpas doradas tan grandes como gatos. Todos alineados en la misma dirección, se deslizan en un inmenso círculo, una lenta y ancha corriente de salmones, esperando el momento exacto en que se lanzarán al riachuelo. Yo nunca había visto tantos salmones y no tenia idea de que fueran tan bellos. Sus cabezas son casi invisibles, verde iridiscente como el agua, pero sus lomos son de un rojo vivido e incandescente. Los peces vienen y van desapareciendo lentamente bajo el bote. Miro a Jon, quien está observando concentradamente.

Las poblaciones de salmón de Alaska están entre las más prístinas del mundo. En los lagos donde trabaja Jon, cada año alrededor de un millón de salmones escapan a las redes y a los botes de pesca, aunque otro millón o dos son capturados. De manera que las densidades que llenan las corrientes, y que vemos, son sólo una fracción de lo que sería la corrida si se le dejara a la naturaleza. Algunas corrientes promediarían más de tres salmones por medro cuadrado en todo su recorrido. Los cientificos estudian este ecosistema como si estuviera intacto, pero nadie sabe cómo luciría un río si no hubiera sido tocado por los humanos.

A pesar de todo esto, mediante el estudio de los ciclos de renovación en Alaska, los cientificos están demostrando lo profundamente que el sistema se ha ido afectando en otros lugares y están comenzando a comprender lo rápidamente que debemos actuar.

Si podemos hallar una forma de reservar y restaurar el hábitat del salmón, reducir la competencia de los criaderos de peces, eliminar los obstáculos para el libre cauce de las corrientes y regular la pesca comercial, de manera que permita que fluyan río arriba suficiente nutrientes derivados del salmón, entonces quizás hallaremos la forma de hacer que el salmón regrese.

Yo he visto salmones nadando río arriba para desovar, aun con los ojos mordisqueados. Aun muriéndose, con la carne cayéndose de las espinas, he visto salmones luchando para proteger sus nidos. Los he visto escalar arroyos tan pequeños que se quedaban varados en la grava. Los he visto nadar río arriba con inmensas dentelladas en sus cuerpos hechas por los osos. Los salmones son increíblemente aferrados al desove. No se rendirán Eso me brinda esperanza.

sábado, 17 de enero de 2009

LIFE CYCLE OF THE SALMON

Spawning Salmon in Becharof Stream within the Becharof wilderness in southern Alaska, USA.

Life cycle of the Salmon

Spawning sockeye salmon in Becharof Creek, Becharof Wilderness, Alaska

Eggs in different stages of development. In some only a few cells grow on top of the yolk, in the lower right the blood vessels surround the yolk and in the upper left the black eyes are visible, even the little lens

Salmon fry hatching - the larva has grown around the remains of the yolk - visible are the arteries spinning around the yolk and little oildrops, also the gut, the spine, the main caudal blood vessel, the bladder and the arcs of the gills

In Alaska, the crossing-over to other streams allows salmon to populate new streams, such as those that emerge as a glacier retreats. The precise method salmon use to navigate has not been entirely established, though their keen sense of smell is involved. In all species of Pacific salmon, the mature individuals die within a few days or weeks of spawning, a trait known as semelparity. However, even in those species of salmon that may survive to spawn more than once (iteroparity), post-spawning mortality is quite high (perhaps as high as 40 to 50%.)

In order to lay her roe, the female salmon uses her dorsal fin to excavate a shallow depression, called a redd. The redd may sometimes contain 5,000 eggs covering 30 square feet (2.8 m2).[1] The eggs usually range from orange to red in color. One or more males will approach the female in her redd, depositing his sperm, or milt, over the roe.[2] The female then covers the eggs by disturbing the gravel at the upstream edge of the depression before moving on to make another redd. The female will make as many as 7 redds before her supply of eggs is exhausted. The salmon then die within a few days of spawning.[2]

Spawning sockeye salmon in Becharof Creek, Becharof Wilderness, Alaska

Eggs in different stages of development. In some only a few cells grow on top of the yolk, in the lower right the blood vessels surround the yolk and in the upper left the black eyes are visible, even the little lens

Salmon fry hatching - the larva has grown around the remains of the yolk - visible are the arteries spinning around the yolk and little oildrops, also the gut, the spine, the main caudal blood vessel, the bladder and the arcs of the gills

In Alaska, the crossing-over to other streams allows salmon to populate new streams, such as those that emerge as a glacier retreats. The precise method salmon use to navigate has not been entirely established, though their keen sense of smell is involved. In all species of Pacific salmon, the mature individuals die within a few days or weeks of spawning, a trait known as semelparity. However, even in those species of salmon that may survive to spawn more than once (iteroparity), post-spawning mortality is quite high (perhaps as high as 40 to 50%.)

In order to lay her roe, the female salmon uses her dorsal fin to excavate a shallow depression, called a redd. The redd may sometimes contain 5,000 eggs covering 30 square feet (2.8 m2).[1] The eggs usually range from orange to red in color. One or more males will approach the female in her redd, depositing his sperm, or milt, over the roe.[2] The female then covers the eggs by disturbing the gravel at the upstream edge of the depression before moving on to make another redd. The female will make as many as 7 redds before her supply of eggs is exhausted. The salmon then die within a few days of spawning.[2]

The eggs will hatch into alevin or sac fry. The fry quickly develop into parr with camouflaging vertical stripes. The parr stay for one to three years in their natal stream before becoming smolts which are distinguished by their bright silvery colour with scales that are easily rubbed off. It is estimated that only 10% of all salmon eggs survive long enough to reach this stage.[3] The smolt body chemistry changes, allowing them to live in salt water. Smolts spend a portion of their out-migration time in brackish water, where their body chemistry becomes accustomed to osmoregulation in the ocean.

The salmon spend about one to five years (depending on the species) in the open ocean where they will become sexually mature. The adult salmon returns primarily to its natal stream to spawn. When fish return for the first time they are called whitling in the UK and grilse or peel in Ireland. Prior to spawning, depending on the species, the salmon undergoes changes. They may grow a hump, develop canine teeth, develop a kype (a pronounced curvature of the jaws in male salmon). All will change from the silvery blue of a fresh run fish from the sea to a darker color. Condition tends to deteriorate the longer the fish remain in freshwater, and they then deteriorate further after they spawn becoming known as kelts. Salmon can make amazing journeys, sometimes moving hundreds of miles upstream against strong currents and rapids to reproduce. Chinook and sockeye salmon from central Idaho, for example, travel over 900 miles (1,400 km) and climb nearly 7,000 feet (2,100 m) from the Pacific ocean as they return to spawn.

Each year, the fish experiences a period of rapid growth, often in summer, and one of slower growth, normally in winter. This results in rings (annuli) analogous to the growth rings visible in a tree trunk. Freshwater growth shows as densely crowded rings, sea growth as widely spaced rings; spawning is marked by significant erosion as body mass is converted into eggs and milt.

Freshwater streams and estuaries provide important habitat for many salmon species. They feed on terrestrial and aquatic insects, amphipods, and other crustaceans while young, and primarily on other fish when older. Eggs are laid in deeper water with larger gravel, and need cool water and good water flow (to supply oxygen) to the developing embryos. Mortality of salmon in the early life stages is usually high due to natural predation and human induced changes in habitat, such as siltation, high water temperatures, low oxygen conditions, loss of stream cover, and reductions in river flow. Estuaries and their associated wetlands provide vital nursery areas for the salmon prior to their departure to the open ocean. Wetlands not only help buffer the estuary from silt and pollutants, but also provide important feeding and hiding areas.

The salmon spend about one to five years (depending on the species) in the open ocean where they will become sexually mature. The adult salmon returns primarily to its natal stream to spawn. When fish return for the first time they are called whitling in the UK and grilse or peel in Ireland. Prior to spawning, depending on the species, the salmon undergoes changes. They may grow a hump, develop canine teeth, develop a kype (a pronounced curvature of the jaws in male salmon). All will change from the silvery blue of a fresh run fish from the sea to a darker color. Condition tends to deteriorate the longer the fish remain in freshwater, and they then deteriorate further after they spawn becoming known as kelts. Salmon can make amazing journeys, sometimes moving hundreds of miles upstream against strong currents and rapids to reproduce. Chinook and sockeye salmon from central Idaho, for example, travel over 900 miles (1,400 km) and climb nearly 7,000 feet (2,100 m) from the Pacific ocean as they return to spawn.

Each year, the fish experiences a period of rapid growth, often in summer, and one of slower growth, normally in winter. This results in rings (annuli) analogous to the growth rings visible in a tree trunk. Freshwater growth shows as densely crowded rings, sea growth as widely spaced rings; spawning is marked by significant erosion as body mass is converted into eggs and milt.

Freshwater streams and estuaries provide important habitat for many salmon species. They feed on terrestrial and aquatic insects, amphipods, and other crustaceans while young, and primarily on other fish when older. Eggs are laid in deeper water with larger gravel, and need cool water and good water flow (to supply oxygen) to the developing embryos. Mortality of salmon in the early life stages is usually high due to natural predation and human induced changes in habitat, such as siltation, high water temperatures, low oxygen conditions, loss of stream cover, and reductions in river flow. Estuaries and their associated wetlands provide vital nursery areas for the salmon prior to their departure to the open ocean. Wetlands not only help buffer the estuary from silt and pollutants, but also provide important feeding and hiding areas.

EL SALMON DEL PACIFICO

Salmón del Pacífico

Los salmones que viven en el norte del océano Pacífico sólo desovan una vez, y mueren tras depositar y fecundar los huevos.

La especie que más se conoce y la más valiosa es el salmón chinook, también llamado salmón real.

Los ejemplares comercializados de este salmón tienen un peso medio de 9 kg, pero muchas especies miden más de 1,5 m de longitud y tienen más de 45 kg. de peso.

El salmón chinook migra a mayores distancias que cualquier otro salmón, recorriendo a veces entre 1.600 y 3.200 km antes de llegar a su territorio de desove.

Sus huevos suelen abrirse en unos dos meses, y las crías nadan hasta el mar cuando alcanzan una longitud de 5 a 7,5 centímetros.

Los salmones que viven en el norte del océano Pacífico sólo desovan una vez, y mueren tras depositar y fecundar los huevos.

La especie que más se conoce y la más valiosa es el salmón chinook, también llamado salmón real.

Los ejemplares comercializados de este salmón tienen un peso medio de 9 kg, pero muchas especies miden más de 1,5 m de longitud y tienen más de 45 kg. de peso.

El salmón chinook migra a mayores distancias que cualquier otro salmón, recorriendo a veces entre 1.600 y 3.200 km antes de llegar a su territorio de desove.

Sus huevos suelen abrirse en unos dos meses, y las crías nadan hasta el mar cuando alcanzan una longitud de 5 a 7,5 centímetros.

viernes, 16 de enero de 2009

jueves, 15 de enero de 2009

THE BLUE REVOLUTION

Blue Revolution

by Marguerite Holloway, Photography by Kristine Larsen

published online September 1, 2002

View through an underwater camera used by technicians monitoring the release of food pellets at a salmon farm near Vancouver. About 50 percent of the protein in the pellets comes from fish meal and fish oil. "Farms are getting more efficient in controlling the amount of feed expended per fish," says aquaculture expert Rosamond Naylor. "But as the industry expands, it will require more wild fish to use as feed for farmed fish."

Last October, Stanford University economist Rosamond Naylor spent four hours flying over the southern part of the state of Sonora, which is half desert, half Sierra Madre mountains, in a crop-dusting plane borrowed for the outing. She was looking for evidence of inland shrimp farms, a burgeoning industry, and expected to find clusters of scattered ponds separated by huge tracts of sere land. Instead, it looked as if the Sea of Cortes had risen and swept across more than 42 square miles of the Sonoran: everywhere patches of blue, pools of shrimp, one after another, all down the coast. "It was so much more developed than I had thought," Naylor says. "The farms are right next to each other."

Over the course of a year, 95 percent of Mexico's farmed shrimp harvest—64 million pounds in 2000—makes its way to the United States. Most of the shrimp Americans consume come from abroad, and chances are excellent that they were farmed in Asia, Central or South America, or Mexico. We are also eating salmon raised on ranches that float in the seas off the coasts of Norway, Chile, Maine, and the Pacific Northwest. Slightly less than one-third of the seafood we consume is not wild at all, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It comes from aquaculture, a $52-billion-a-year global enterprise involving more than 220 species of fish and shellfish that is growing faster than any other food industry—so fast that fish farming is expected to exceed beef ranching within a decade.

This blue revolution could help solve some big problems. It could provide fish for an ever-growing number of consumers and more food for the 1 billion chronically malnourished people worldwide who need protein. And it could do so while saving rapidly disappearing wild fish by relieving the pressure of commercial fishing. But Naylor is one of a group of scientists and environmentalists who are not convinced that aquaculture is beneficial. She contends that in many places, the practice is destroying land along coasts and causing water pollution. And instead of helping save wild fish, she argues, aquaculture may actually be hastening their demise. "To say that aquaculture shouldn't happen at all would be wrong," she says. "But right now aquaculture is a slash-and-burn activity, shrimp farming in particular."

(A) A typical shrimp farm in the southern Sonoran Desert of Mexico covers nearly 250 acres. (B) Four-month-old shrimp will be harvested within another two months. (C) "Disease can spread quickly between closely linked ponds," says Naylor, on a tour with locals who fish for shrimp the old-fashioned way.

Naylor is convinced that these improvements could help the blue revolution succeed in areas where the green revolution failed. Given the diversity and global character of the industry, she has set her sights high. But consider this: She has seen a desert turn first green and now blue, and she has seen crustaceans swimming amid cacti. In the light of such wonders, anything seems possible.

Goldburg, Rebecca J., et al. "Marine Aquaculture in the United States: Environmental Impacts and Policy Options." Pew Oceans Commission, Arlington, Va., 2001. Available online at www.pewoceans.org/oceanfacts/2002/01/11/fact_22988.asp.

THE GIFT OF SALMON

The Gift of Salmon

In Alaska, biologists are learning that when wild salmon are free to swim upstream to spawn, dozens of other species flourish too

by Kathleen Dean Moore and Jonathan W. Moore, Photograph by Art Wolfe

published online May 1, 2003

My son and I splash upstream in hip boots, searching for signs of the sockeye salmon that return each summer to spawn and die in this wild Alaskan creek. I've come here to see for myself what he wrote home about last year:

The creek is so full of sockeye, it's a challenge just to walk upstream. I stumble and skid on dead salmon washed up on the gravel bars. It's like stepping on human legs. When I accidentally trip over a carcass, it moans, releasing trapped gas. In shallow water, fish slam into my boots. Spawned-out salmon, moldy and dying, drift down the current and nudge against my ankles. Glaucous-winged gulls swarm and scream upstream, a sign the grizzlies are fishing. The creek stinks of death.

These sockeye salmon are swimming upstream to spawn. In Alaska, salmon still abound, but in the lower 48 many runs have been decimated by dams, habitat degradation, and overfishing. The Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest was once teeming—2,112,500 salmon were caught in 1941; by 1998, the catch had dwindled to only 67,200 fish.

In Alaska, biologists are learning that when wild salmon are free to swim upstream to spawn, dozens of other species flourish too

by Kathleen Dean Moore and Jonathan W. Moore, Photograph by Art Wolfe

published online May 1, 2003

My son and I splash upstream in hip boots, searching for signs of the sockeye salmon that return each summer to spawn and die in this wild Alaskan creek. I've come here to see for myself what he wrote home about last year:

The creek is so full of sockeye, it's a challenge just to walk upstream. I stumble and skid on dead salmon washed up on the gravel bars. It's like stepping on human legs. When I accidentally trip over a carcass, it moans, releasing trapped gas. In shallow water, fish slam into my boots. Spawned-out salmon, moldy and dying, drift down the current and nudge against my ankles. Glaucous-winged gulls swarm and scream upstream, a sign the grizzlies are fishing. The creek stinks of death.

These sockeye salmon are swimming upstream to spawn. In Alaska, salmon still abound, but in the lower 48 many runs have been decimated by dams, habitat degradation, and overfishing. The Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest was once teeming—2,112,500 salmon were caught in 1941; by 1998, the catch had dwindled to only 67,200 fish.

Jon's notes describe the feeding frenzy when the salmon are spawning: On the banks of the salmon stream, we come across bear kitchens, trampled ferns and grasses and decomposing salmon parts, where the bears dragged salmon to eat. Gulls have a hard time breaking open salmon skin by themselves, so flocks of gulls follow the bears, waiting to swoop in and swallow up leftovers. Gulls nest on exposed islands that quickly become littered with salmon bones. As the chicks grow fat, the island is whitewashed with digested salmon. Rain washes guano into the lake. Bald eagles rip into salmon and carry the food to their chicks. Caddis flies feed on salmon carcasses underwater, then hatch into adults that take to the air. Rainbow trout feed on salmon flesh that slowly breaks free from decomposing carcasses. Mink gorge on spawned-out fish. Trees grow rapidly with all this fertilizer. Tourists buzz in on floatplanes to fish, throwing the guts to gulls and freezing fillets in waxed cardboard cartons to be flown back to Tacoma or St. Louis.

www.sierraclub.org/wildlands/species/salmon.asp.

At least 66 species in the Pacific Northwest seek salmon for sustenance, feeding on the eggs, carcasses, and every life stage in between.

www.sierraclub.org/wildlands/species/salmon.asp.

At least 66 species in the Pacific Northwest seek salmon for sustenance, feeding on the eggs, carcasses, and every life stage in between.

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)